By David Abel | Globe Staff | 7/07/2003

When a judge asked one man to name the US president, he responded: "Osama bin Laden." Another judge confronted a defendant so mentally disturbed he had chased neighbors with a samurai sword. Then there was the man whose landlord found him aimlessly walking through traffic beside his building.

Housing court judges have long grappled with how to evict mentally or physically disabled tenants without sentencing them to life on the streets. The law requires the court to find "reasonable accommodation" for the disabled, but because of budget cuts and a shrinking social safety net, an eviction ruling often has meant homelessness.

Now, for the first time, judges are successfully persuading landlords to keep their disabled tenants. Their new weapon: teams of social workers in Boston, Brockton, Springfield, Northampton - and soon, other parts of the state - who make sure the mediation sticks, even if it means they have to drive tenants to court hearings, spoon-feed medication, or clean up cluttered apartments themselves.

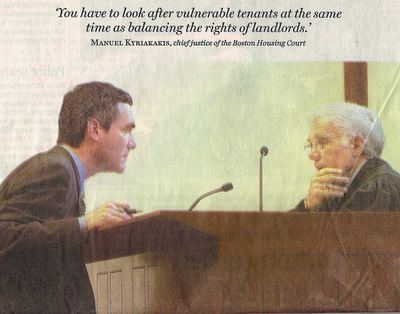

"These are difficult cases, where you have to look after vulnerable tenants at the same time as balancing the rights of landlords to preserve their property and protect their other tenants," said Chief Justice Manuel Kyriakakis of the Boston Housing Court. "But now with this new program, for the first time, we have a real ability to render reasonable accommodation."

The Tenancy Preservation Project began a few years ago at the housing court in Springfield, which like the one in Boston hears thousands of eviction cases a year. The program in Boston, which received $162,000 in state and city aid last year, made a modest start in September. Judges asked the program's three social workers to intervene in 24 cases, half of which have been resolved with tenants remaining in their apartments.

The social workers' help ranges from mundane tasks, such as finding a state agency that will provide money for a tenant's medication, to grittier jobs such as clearing rat-dung, cobwebs, and mildew from apartments so grimy that cleaning services won't enter them.

"The main thing we do is try to make sure people don't fall through the cracks," said Ruth Harel, who runs the Boston program and frequently visits tenants to ensure they're taking their medication, paying their rent, and otherwise complying with agreements she has helped negotiate with their landlords. "The overall goal is to prevent homelessness."

There are limits to the program, which court officials plan to spread to Worcester and Lowell this fiscal year. It is voluntary, and some mentally ill defendants deemed competent to stand trial refuse the help. Also, the state aid covers only those disabled tenants in subsidized apartments.

But the program's success has convinced even skeptical landlords. In the beginning, court officials say, many landlords feared the program would favor tenants. Now, lawyers who represent landlords say that many realize a fair compromise can mean not having to bear the cost of evicting someone and finding a new tenant.

When the new system works, the cases look like the compromise reached between Katherine Ross and her landlord in Dorchester. A few months ago, the 80-year-old former nurse, who suffers from arthritis and a heart condition, received an eviction notice. Her landlord said she had too much stuff in the one-bedroom apartment where she has lived for the past 21 years, creating a fire hazard and a maintenance problem. After a judge referred the case to the Tenancy Preservation Project, social workers and the landlord arrived at a solution: Ross could stay if she had the apartment cleaned, put many of her things in storage, and cleared some space by the entrance.

But, no matter how much help social workers offer, some cases can't be solved through compromise. Housing court judges, for example, rarely seek such solutions for disabled tenants found with illegal drugs, those known for violence, or those who refuse to pay their rent, which can disqualify them from subsidized housing.

Then there are the cases of tenants such as Heidi K. Erickson, a.k.a. the Cat Lady, whose squalid Beacon Hill apartment city inspectors condemned after finding dozens of diseased and dead felines there. When her case came before Judge Kyriakakis earlier this year, he referred it to the social workers. But Erickson refused to let them help, he said. She was deemed competent to represent herself, and the judge convened a trial and ordered her to move out.

On a recent day at the courthouse on New Chardon Street, Vickey Barnes was hoping the system would rescue her and her two sons. Her landlord wanted her out, alleging she has broken windows, bored holes in the walls of her Roxbury apartment, and disturbed neighbors by screaming.

The judge referred the case to the social workers, and the landlord's lawyer offered a compromise: If she agreed to eviction, she would have three months to leave. If she fought it and lost in court, she would have to move as soon as the judge ruled against her.

Barnes didn't think it was a fair deal, so she turned it down. The judge set a date for trial this summer. The social workers promised to use the time to press the landlord to find a solution.

"I don't have nowhere else to go," said Barnes, 41. "I hope they help me keep my apartment."

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com. Follow him on Twitter @davabel.

Copyright, The Boston Globe