Cash-Strapped Seniors Scrimp While Holding Valuable Property

Cash-Strapped Seniors Scrimp While Holding Valuable PropertyBy David Abel | Globe Staff | 8/03/2001

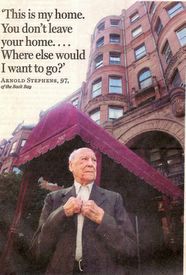

Arnold Stephens could sell his Back Bay home and stash a half-million dollars in the bank. Instead, the 97-year-old man eats in soup kitchens and hitchhikes to get around.

Nearly every day, Stephens shuffles out of his Beacon Street brownstone in a rumpled suit, sticks out his thumb, and asks strangers to drive him to the T, the Prudential Center, or one of the churches he frequents for free meals.

With no savings and only about $14,000 a year from his pension and Social Security, Stephens is one of about 2,100 elderly homeowners in Boston - and nearly 24,000 in Massachusetts - who find themselves sitting on property so valuable they need help just to pay the tax.

In 1974, Stephens bought his two-bedroom condominium for $30,000, and since then the real-estate market has boomed. The city now assesses it at $359,000, though realtors say it could fetch far more in today's market.

"People are crazy about what they're willing to pay for a little apartment - just crazy," says Stephens, whose property taxes have risen to nearly $4,000 a year. "But this is my home. You don't leave your home. Besides, this is the center of the universe. Where else would I want to go?"

Stephens may be an extreme case. But Leo Moss, a coordinator of the city program that provides free home repair services for the elderly, says he sees hundreds of older homeowners struggle to pay soaring taxes and rising utility bills.

"A lot of these people would rather die than move," he says. "People get attached to their surroundings. Their homes are part of their lives."

Many of the homeowners Moss helps are like Mable Huggins, a 71-year-old widow living on an income that doesn't cover her mortgage and medical bills. The owner of a seven-bedroom house in Dorchester for the last 22 years, Huggins says her taxes have jumped more than $200 a month in the past few years.

"I'm sick, I'm struggling, but I won't ever move," she says. "Rents are even higher than my mortgage."

To keep people like Huggins and Stephens from being forced out of their homes, the state allows low-income seniors to deduct a portion of their property taxes. In Boston, homeowners over age 70 are eligible if their income falls below $16,350. Stephens has $1,500 of his taxes waived. (State and federal grants cover the city's lost tax revenue.)

Although property values, and taxes, have been rising for a decade, officials say the number of people in Massachusetts seeking deductions has declined by more than 7,000 since 1995, as fewer elderly people live in poverty.

Another state program allows older, low-income homeowners to defer nearly all their property taxes until they sell or die. But few have taken to the program. In Boston, only 10 people have signed up, city officials say.

"It's really a shame," says Ellen Docharty, director of the city's Taxpayer Referral and Assistance Center. "There are a lot of people like Mr. Stephens who would qualify for these programs. They just don't know about it."

Few of them, however, are as land-rich and pocketbook-poor as Stephens. His condo is worth about twice as much as the average home owned by a recipient of the tax waiver.

"Unequivocally, this is a rare case," says Tim Marsh, a broker who publishes Real Estate Insider, a newsletter about market values and trends in Boston. "With the rise in the market, few people hold onto their condos for more than a few years. Mr. Stephens could do very well if he sold."

But he has no plans to move.

He has lived in his brownstone at Beacon and Exeter streets since 1958.

When their building was divided into condos in the 1970s, he and his wife bought a four-room unit on the first floor. She died in 1980 and today he shares the home with Janna Bruins, a 68-year-old retired lab technician who has rented a room from Stephens since 1958. Stephens never had children; his only relatives are three nephews.

When their building was divided into condos in the 1970s, he and his wife bought a four-room unit on the first floor. She died in 1980 and today he shares the home with Janna Bruins, a 68-year-old retired lab technician who has rented a room from Stephens since 1958. Stephens never had children; his only relatives are three nephews.Inside the condo, the paint is peeling, but he strolls out every day beneath the word "Royal" embroidered on the burgundy awning outside the building. Some of his neighbors are paying down mortgages worth more than a million dollars, but Stephens finished paying his years ago.

Molded by the Depression, the retired Raytheon machinist takes pride in his thrift in the neighborhood of the $9 martini.

"You have to go through the Depression, I think, to understand the meaning of the dollar," he says. "I squeezed the nickel so hard I could make the Indian ride the buffalo on the other side of the coin."

Why would a man his age hitchhike? Stephens laughs: "I don't drive," he says. "A man has to get around. People are nice. They're all my friends."

Over the years, Stephens says, he has grown to enjoy eating at soup kitchens. "Fellas like me don't feel like cooking - and some of us wouldn't eat otherwise," he says. "It's also free."

He calls the Friday-night supper at the Arlington Street Church "The best restaurant in town."

Digging in recently to a meal of soup,

chicken salad, potato chips, and chocolate-chip cookies, Stephens swigs a cup of punch and says, "It's just excellent. I don't know what it is, but it is good."

chicken salad, potato chips, and chocolate-chip cookies, Stephens swigs a cup of punch and says, "It's just excellent. I don't know what it is, but it is good."With no plans to convert his valuable asset into a lifetime of restaurant meals, he says he'll keep pinching pennies and going to the soup kitchen. Moving, he says, would be too much trouble. Besides, he adds, there isn't enough affordable housing - and he loves the Back Bay.

Climbing the church steps to head to his home a few blocks from upscale eateries like the Capital Grille and the Armani Cafe, Stephens stops and points to his plastic bag filled with leftovers.

"The food is good, the feelings are good, it's quiet, there's a prayer," he says. "What else could a guy ask for?"

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com. Follow him on Twitter @davabel.

Copyright, The Boston Globe