By David Abel | Globe Staff | 7/19/2002

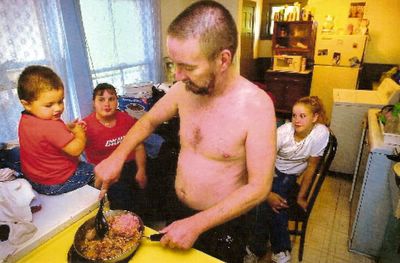

DESPITE the chaos of caring for his two girls and a grandson, Mark Foster cuts a lonely figure.

As a single father on welfare, who sleeps on a couch and survives on food stamps, he says he's often greeted with hostility or disdain by social workers, whose clients are usually single mothers, many abused and deserted by men.

Long after gaining custody of his children, he says, incredulous state officials repeatedly harassed him for child support payments and provided public housing to his ex-girlfriend - not to him - even though she was the one who deserted the family. He was also once cut off public aid, he says, when social workers suggested that because he is a man who can work, he should be able to provide for his family.

"There's definitely a feeling of prejudice you get being a single dad on welfare," says Foster, 39, of Worcester, who works odd jobs. "Nobody wants to do nothing for you. And you feel weird, out of place, alone, and like you shouldn't be there every time you go to the welfare office."

As the number of single fathers increases and the percentage of men collecting welfare rises, more men are complaining about bias in a system that has long catered to women, social workers, and researchers in the field say.

Today, more than 3 million of the nation's men are singlefathers, triple the number of two decades ago, and they now represent 16 percent of all single parents. Only a small number of those collect welfare, but as single mothers are increasingly cut off from public aid, the percentage of men is climbing. In Massachusetts, 6 percent of the 47,000 welfare recipients are men, up from 4 percent a decade ago.

As Congress considers putting more welfare recipients to work, able-bodied men like Foster are likely to be among the first pushed into the job market, and perhaps the first to complain of unfair treatment. While only 6 percent of welfare recipients in Massachusetts work, legislation that recently passed the US House is likely to require 70 percent to find jobs.

"The discrimination is a result of many agencies not used to dealing with men," says James Levine, director of the fatherhood project at the Families and Work Institute in New York. "That creates a built-in bias and it's not uncommon to hear about guys having to jump through hoops that women haven't had to."

Like Foster and other single fathers, Lee Hutchins says he has long been treated by social workers as if he were lying.

Now off welfare nearly a decade after gaining custody of his children, the 36-year-old father of three from Springfield says he was constantly told, "You're a man; you should be working."

"Every time I turned around there was some kind of problem," he says. "They said I was working too many hours, I wasn't working enough hours, I have to participate in programs. They even wanted me to leave a part-time job to participate in a job-search program."

Complaints from recipients, male and female, are common.

"I don't know anyone on welfare who particularly relishes the contact with the department," says Dick Powers, a spokesman for the Department of Transitional Assistance, which oversees the state's welfare programs. "I'm certain that both males and females feel victimized and discriminated against, when in fact caseworkers are merely doing their jobs."

But as the number of men winning custody of children slowly rises, largely the result of drug abuse and jail sentences among women, researchers say there's an institutional problem that must be corrected.

Social workers aren't used to dealing with male welfare recipients and often distrust them.

"Men get a really hard time; even women on welfare believe they should be working," says Elizabeth Lion, a spokeswoman for the Doe Fund, a large social service provider for single men in New York. "There's really a stigma and it's usually a bad rap for no reason."

Because there are relatively few men on welfare, about 2,800 in Massachusetts, there has been little research into their complaints.

The prejudice is palpable, some say.

Julio Tirado, a single father of four from Worcester, said he feels like he is failing as a man when he walks into a welfare office.

"There's total prejudice; the women are always asking why I'm there, why I can't take care of my family," says Tirado, 39, whose wife died of cancer. "It makes you feel bad about yourself, kind of a hit to your masculinity."

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com. Follow him on Twitter @davabel.

Copyright, The Boston Globe