Federal Figures on Unemployment Do Not Include The 'Discouraged'

Federal Figures on Unemployment Do Not Include The 'Discouraged'By David Abel | Globe Staff | 8/21/2003

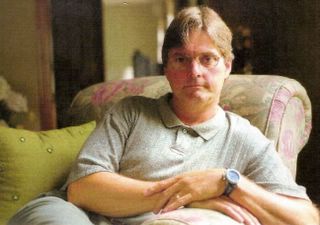

Nearly a year ago, Brian Lupaczyk lost his job after nine years of earning a six-figure salary. Last week, he exhausted his unemployment benefits. Now, depressed about his fruitless search for work, he grumbles: "If I applied for a job at Home Depot, I'm not sure they'd be interested."

Still, the federal government doesn't consider him unemployed.

Lupaczyk, a 48-year-old father of a college junior who shoulders a hefty mortgage for his four-bedroom home in Franklin, is one of a growing number of Americans whom the federal government calls "discouraged workers," or those who haven't looked for work in at least a month.

Even as the economy shows signs of new life, the number of discouraged workers has nearly doubled to half a million since 2000 - helping to account for a drop in the nation's unemployment rate in July. If the government had added Lupaczyk and other discouraged workers to the total, the unemployment rate would have risen to 6.5 percent, instead of fallen to 6.2 percent.

"Typically, in a weakened economy, we see college graduates trade unemployment for underemployment," said Paul Harrington, associate director of the Center for Labor Market Studies at Northeastern University. "But when a lot of people bump down - and some refuse to - people end up getting bumped out of the economy."

For Lupaczyk, in a few weeks a job at Home Depot may no longer be a wistful joke; it may be a necessity.

In October, when he lost his $125,000-a-year job as a project manager at Fidelity Investments, he thought that with his years of experience and many contacts in the field, it wouldn't take long to find a similar job.

His first volley of resumes landed him two interviews. But the good vibes didn't last. Because of the slow economy, both companies eliminated the positions.

Still, with steady unemployment checks and a few months' worth of severance pay, he had a cushion, and he kept at it - up early every day and at his desk, often for 10 hours straight, he would scroll through websites, posting queries on some and finding names on others.

In a typical day, he said, he would send out 10 resumes and make 10 calls.

But the months went by and nothing happened.

"This is the first time I'm out of a job since I was 8, when I had a paper route," he said. "I kept thinking the economy would get better, and it just hasn't. Talk about discouraging."

Of about 150,000 jobs cut in Massachusetts since the start of 2001, nearly half were technology-related positions like the one Lupaczyk lost, according to the state Division of Employment and Training. In the same time, twice as many state residents - now about 85,000 people - have resorted to "involuntarily part-time" work, often giving up professional jobs for service ones at places like Home Depot.

The falloff in jobs has translated into a longer time on unemployment. Between 2000 and 2002, the average number of weeks the state's jobless spent collecting unemployment benefits nearly doubled to 18 weeks, according to the Center for Labor Market Studies. And last year, 31,000 more people left Massachusetts than moved here, the highest level since the recession of the early 1990s.

By the start of summer, with most hiring managers on vacation and the competition for the few available jobs daunting, Lupaczyk had all but given up on finding a job. Over the past few months, he and his wife, who earns a small income as a hairdresser, have been struggling to meet their monthly expenses of roughly $4,000, which include mortgage payments, car loans, food, gas, insurance, and medical expenses.

Aware of his tight budget - the couple now lives off roughly $15,000 in savings, a sum that won't last long - Lupaczyk's former wife has temporarily taken over paying for their son's college education, and he and his current wife have all but abandoned their social lives. Since October, they haven't been to the movies, taken a vacation, or dined at a restaurant. They've gone from aggressively paying down their loans to paying the bare minimums.

"This can be a very depressing lifestyle," Lupaczyk said.

Others are worse off.

The category of discouraged workers - those who have not actively sought a job in the four weeks preceding the government's monthly survey - is just a subset of a larger number of jobless workers who aren't counted in the nation's unemployment figures. The larger category, called "marginally attached" workers, last month included three times as many people, or nearly 1.6 million potential workers who haven't given up looking for work but cite reasons ranging from a lack of child care to transportation problems for their lack of success in landing a job.

And among the 8,000 discouraged workers in Massachusetts, there are those such as Bill Masson, who was so depressed after months without work that he was driven to taking antidepressants to relieve his anxiety. The 60-year-old from Littleton, a former six-figure-salary employee of a technology company, said he has "burned out" his network of contacts and given up on all the job-hunting techniques he learned from previous job searches.

"It just got to the point, for my own sanity, I couldn't keep going on," said Masson, who has remortgaged his home to survive and now spends his days working on home improvements. "I was driving myself crazy."

Unemployment has provided Masson with the opportunity to concentrate on self-improvement. In addition to keeping his lawn freshly mown, he has found the time to exercise; since losing his job, he has lost 30 pounds and seen his cholesterol level plunge more than 75 points. He's also had more time to ride his motorcycle.

Of course, the perks of unemployment, he said, don't outweigh the benefits of having a steady income - and a place to go to every workday. Still hopeless about the prospects of finding employment anytime soon - at least not at the level he'd like - he's considering posting an ad in the local newspaper, hoping neighbors might hire him to set up their home computers.

"It's not a living, but who knows, maybe it will become one," Masson said. "It's the only thing that's giving me any hope."

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com. Follow him on Twitter @davabel.

Copyright, The Boston Globe