Free Care for Needy Foreigners Clash With Reality of Struggling Health System

By David Abel and Alice Dembner | Globe Staff | 9/26/2002

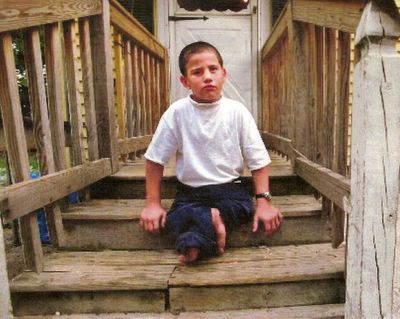

Smiling shyly, the paraplegic 11-year-old boy shows how he uses his thick, calloused hands to move around, enabling him to earn about a dollar a day shining shoes back home in Honduras. He has come to Boston for an operation on his legs, he says, "so I can walk to school."

After six months here seeking surgery and prosthetics, with the backing of the persistent pastor of a Jamaica Plain church, Noel Ramirez has learned how to speak and smile to win doctors over.

Over the past decade, using videos or escorting sick children like Ramirez, Rubenia Bomatay has made emotional appeals to Boston-area hospitals that have secured hundreds of thousands of dollars in free treatment for at least a dozen poor patients her church has flown up from Latin America.

"I know it well that there isn't money, that we need insurance, and that the state has no requirement to pay for these operations," she says. "I just ask God that he will help him. I know, legally, that the hospital doesn't have to do anything. But they do often, and we are very thankful for that."

Local hospitals provide hundreds of millions of dollars worth of free care annually to needy patients, and some have programs to treat groups of foreign patients from medical trouble spots. And the hospitals direct most free care to US residents, especially at a time when budget cuts are slashing social services.

Still, as Bomatay has found, few are willing to turn away a desperate foreign patient on their doorstep. The 47-year-old pastor has made an art out of obtaining free care for patients, ranging from open heart surgery and the removal of cancerous tumors at major hospitals to free medicine at health clinics.

Though doctors and health care advocates say Bomatay's tactics are unusual, some worry that - however well-intentioned her efforts - her success may come at the expense of US patients in an overburdened system.

"I think it's a heroic thing to bring families here who are disadvantaged," says Rob Restuccia, executive director of Health Care for All, an advocacy group. "But the fact of the matter is that we can't sustain it, especially with 50,000 residents being thrown off Medicaid. We're in a health care crisis and we have to be careful where our dollars go."

It didn't take long for Bomatay to figure out how the system could work for impoverished visitors.

Shortly after moving to Boston from Honduras in 1994, her blood pressure began to rise and one of her children, who had become a US citizen, took her to Boston Medical Center. She stared in awe at the technology and at the contrast with hospitals in Honduras. "It gave me a lot of sadness for my country," she says.

Then the bill came. But to her surprise, the doctors told her she shouldn't worry. They had ways to cover the expense for patients without insurance or residency. The free care and impressive service gave her an idea: "It made me realize that I had to help my people, those who really needed the help," she says.

But things haven't always gone so smoothly. Some of the patients her church has brought to Boston have spent months seeking free care. Martiza Soto, a 28-year-old Honduran who spent eight months here seeking treatment for mouth cancer, returned home without the needed operation - and eventually died.

For Ramirez and his mother, Ursolina, it's been a long wait since they arrived in March with tickets and visas obtained through Bomatay's church, La Iglesia Reformada Emanuel in Jamaica Plain. Ursolina left six other children with relatives at their cramped home in Teopacenti, a small town in southern Honduras.

Soon after arriving,

Noel saw Dr. Michael J. Goldberg, a pediatric orthopedist and chairman of orthopedics at Tufts-New England Medical Center, who agreed to waive his fees for the evaluation. Goldberg found Ramirez was missing a bone in each leg and needs amputation of his deformed bones and feet to fit prosthetic legs. Although Goldberg was willing to do free surgery, the hospital rejected the boy's application for free care and referred him to the Shriners, whose mission is to provide free care to children.

Noel saw Dr. Michael J. Goldberg, a pediatric orthopedist and chairman of orthopedics at Tufts-New England Medical Center, who agreed to waive his fees for the evaluation. Goldberg found Ramirez was missing a bone in each leg and needs amputation of his deformed bones and feet to fit prosthetic legs. Although Goldberg was willing to do free surgery, the hospital rejected the boy's application for free care and referred him to the Shriners, whose mission is to provide free care to children."On occasion, the empathy of the physician and the business reality of the health system are not in synch," Goldberg says. The operation and prosthetics would cost tens of thousands of dollars.

At Children's Hospital, doctors said they were concerned about making the boy's condition worse in the long run. "He needs a plan for the rest of his life," said Dr. James Kasser. "He'll wear out the prosthetics every few years or he'll grow out of them. Then he might be worse off."

Ramirez took the rejections hard. "The boy was crying every day and he thought nobody wanted him," says his mother, who is staying with Noel at Bomatay's home in Dorchester.

But Bomatay's persistence paid off this week on at least one front: Doctors at Boston Medical Center performed another much-needed operation on the boy, freeing an undescended testicle.

BMC, which provides the most free care in the area - $226 million in the last fiscal year - rarely turns away patients in need of treatment, especially children. "Our job, as we see it, is to care for children who come to see us," says Dr. Barry Zuckerman, chairman of BMC's pediatrics department.

The medical center put his request for leg surgery on hold while the Shriners Hospital in Springfield considered Ramirez's case. That hospital specializes in orthopedics, treats about 120 foreign children a year, and has an affiliate in Mexico City.

In the end, it's likely the Shriners will treat the boy, says hospital administrator Mark Niederpruem, but the decision rests with its doctors.

While he waits, Ramirez spends most of his time watching television and playing with Bomatay's younger children, picking up a few sayings in English.

But most of all now, he dreams about returning home as a new boy, taller and more mobile.

"I would really like to be able to walk," he says. "It would make it easier for me to help my mom."

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com. Follow him on Twitter @davabel.

Copyright, The Boston Globe