State Seeks to Bring Down Illegally High Interest Rates

State Seeks to Bring Down Illegally High Interest RatesBy David Abel | Globe Staff | 5/01/2003

FALL RIVER - The switchblade didn't sell, so the welfare recipient took off two gold rings her daughter had given her and pawned them for a $10 loan. When an unemployed carpenter got only $40 for a sack of old coins his great-grandfather collected in World War I, he hocked his diamond wedding band for $30. And after a cash-short telemarketer bounced a check, it was time to bring in his DVD player.

"I wouldn't say this is a good deal, but it helps in a bind," said Chris Nygren, 31, who got a $45 loan for his DVD player and 13 of his favorite movies. Like the others, the loan comes with a stiff interest rate: 10 percent a month.

Though scores of similar transactions occur nearly every day here at New England Pawnbrokers and the city's other pawnshops, state officials say they're illegal and must stop.

The high-interest loans pawnshops charge are nothing new, but after years of ignoring a century-old law requiring the Massachusetts Division of Banks to approve interest rates in every city and town, the state has launched a crackdown.

Adding pressure on the state's pawnshops, Representative John F. Quinn, a Dartmouth Democrat and cochairman of the Legislature's Joint Banks and Banking Committee, recently proposed a bill that would set significant limits on the interest they can charge and raise fines for those violating the law.

"It's egregious what some of these pawnshops are charging some of the most desperate people," said Quinn, who took action after learning that in February, Fall River's City Council voted to permit local pawnbrokers to continue charging 120 percent interest a year - the highest rate of any municipality in the state. Quinn's bill would cap interest rates at 36 percent per year.

In March, officials at the Division of Banks sent a letter to Fall River, telling the mayor and council members that their city's pawnshops would be breaking the law if they continued charging any interest. They can't resume making loans, officials said, until there's a public hearing and the banking commissioner rules on the city's new interest rates, a process that could take months.

The pawnshops' reaction? Ignore the state.

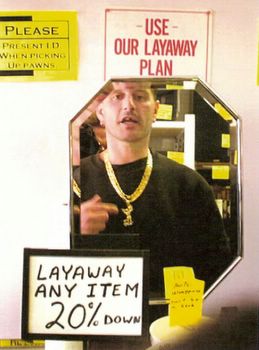

"They're trying to put us out of business," said Paul Wilner, who opened New England Pawnbrokers less than a year ago and says his South Main Street shop has yet to turn a profit. "We have to earn a living."

Wilner, who runs his pawnshop with his wife, justifies their interest rates by comparing their revenue with those in larger cities such as Boston, where similar shops thrive just charging 3 percent a month in interest. The shops in larger cities have more foot traffic. With only 90,000 people in Fall River, compared with seven times that in Boston, he says the higher interest rates are needed to make ends meet.

The couple, who earn most of their money making loans, say they take in about $28,000 in loans a month. However, they say their profit is only about $3,800, roughly a quarter of which comes from their $5 initial loan fees for jewelry. They also make money from selling all the things - televisions, Barbie dolls, guitars, family heirlooms - their customers give up by defaulting on their loans.

After they pay $1,000 a month in rent for their small, cramped shop, and their many other expenses - including police confiscation of stolen items - the Wilners insist their overall take-home isn't much, and anything but usurious. "We're not going to get rich here," said Linda Wilner, adding she often cuts her clients some slack and believes she provides a crucial service to those desperately in need of cash. "We don't have any vacations planned to Hawaii."

City officials, however, are starting to rethink their support for the 120 percent annual interest rate - which pawnbrokers in Fall River and other unregulated municipalities have charged for years.

"I thought the 10 percent [interest] was for a year, not for a month," said Joseph Camara, the City Council's president, adding he expects council members will revisit the issue. "I don't think we were hoodwinked, but maybe I didn't pay as much attention as I should have. I think 10 percent a month is a little steep."

After long ignoring the 1902 law regulating pawnshops, state officials rediscovered it three years ago when commissioners at the Division of Banks learned a Revere pawnbroker had been illegally taking car titles as collateral for loans.

After that, commissioners surveyed the state's 351 towns and cities to compare interest rates. They found most had no regulations. Since then, they've told all those municipalities with pawnshops that they must set a local interest rate and then have it approved by the Division of Banks.

So far, commissioners have approved interest rates for only six municipalities - Revere, Lawrence, and Somerset at 36 percent a year, Quincy at 24 percent, Chicopee at 18 percent, and Cambridge at 13 percent. At least seven other communities are still waiting for approval, including Fall River and Boston, which is seeking to increase its rate to 60 percent a year.

But until commissioners approve their municipality's interest rates, the pawnshops are operating illegally, said David Cotney, senior deputy commissioner at the Division of Banks. "People do stuff outside the law; I'm not blind to that," Cotney said. "But we're trying to make people comply with the law. We've made our decision clear: Until interest rates have been approved, charging interest is not authorized."

The state's new interest in regulating pawnshops has peeved Ed Bean, chairman of the board of Massachusetts Pawnbrokers Association. Compared with other states such as Florida and Texas - which he says allow their pawnshops to charge as much as 20 percent interest a month - Massachusetts already has some of the lowest rates.

If the Legislature votes to set a cap on interest rates at 3 percent a month, he expects about half of the state's 57 pawnshops to close.

"Why should we have the lowest interest rates in America?" Bean said. "What the commissioners are doing is wrong - and it will hurt the people they're trying to protect. When they need money, they'll have to sell their things instead of loaning them."

At New England Pawnbrokers, where two large German shepherds keep a close watch on the customers, Joy Covel seemed nonplussed when the shop's appraiser wouldn't buy her switchblade, necklaces, or bracelets. So when the 44-year-old pawned the gold rings her daughter gave her 15 years ago, she said she would use the $10 loan to buy milk and cigarettes. "I like having money in my pocket," she said.

If Covel was satisfied by her deal - in a month, she'll have to pay the pawnshop $16, the 10 percent interest plus the $5 base fee for pawning jewelry - Eddy, the 33-year-old unemployed carpenter, was less than enthusiastic.

Having pawned his wedding band and sold his great-grandfather's collection of century-old coins, the father of three grumbled about not having "some hidden treasure" that would have padded his wallet a bit more.

"Do I think this was a fair deal? Definitely not," said Eddy, who would only give his first name. "But what else can I do?"

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com. Follow him on Twitter @davabel.

Copyright, The Boston Globe