By David Abel | Globe Staff | 1/13/2003

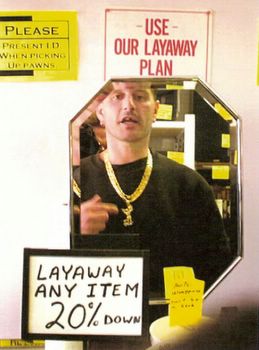

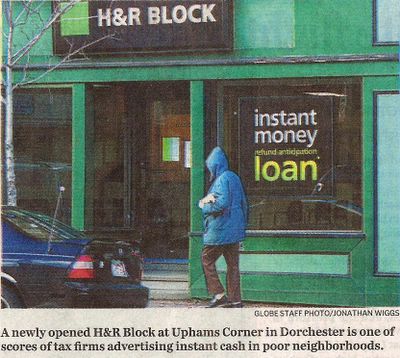

On a gritty block lined with timeworn storefronts, the big bright sign in the freshly scrubbed window looms like a beacon to the neighborhood's poor. In bold letters, it reads: "Instant Money."

Mary Williams drops into the newly opened H & R Block branch on Uphams Corner and emerges with what she sees as a good deal. Rather than file her federal tax return herself, and wait perhaps two months to claim her tax credit, the 21-year-old mother will return to the Dorchester branch in three days and pick up a check - minus a fee of $200 or more.

"Christmas broke me," said Williams, after leaving the branch on a recent night. "I need the money - I've got bills, kids, and life to take care of now."

One of about 40,000 Bostonians who will benefit from the Earned Income Tax Credit - the landmark federal effort to pump extra money into low-income working households - Williams is among a quarter of those city residents who will give tax firms like H & R Block a significant portion of their often desperately needed refunds.

With scores of such firms now opening branches in the city's poorest neighborhoods, many of them similarly advertising instant cash - really loans with interest rates often exceeding 100 percent, if the money were borrowed for a full year - city officials are joining a national campaign this week to persuade residents this tax season to shun what they consider "usurious" business practices that unfairly target the poor.

After all, the average recipient gets about a $1,500 refund, and giving up $200 or more defeats the purpose of a program both Republicans and Democrats have long touted as one of the most effective ways to help the poor.

"The purpose of this tax credit is to lift poor people from poverty, not to line the pockets of tax firms," said Mimi Turchinetz, the city's living-wage administrator, who is hoping to steer residents to 16 sites around Boston providing free tax help. "Given what these firms charge and how they lure people, it's easy to argue they're preying on the poor."

Although studies show

tax firms open more than half their offices in the nation's poorest neighborhoods - in 2000, according to a zip code count, a third of all those in Boston were in Roxbury, Dorchester, and Mattapan - officials at firms such as H & R Block insist they're not targeting the poor. "A lot of the criticism is unfair. What we do is give our clients options," said Denise Sposato, a spokeswoman for H & R Block.

tax firms open more than half their offices in the nation's poorest neighborhoods - in 2000, according to a zip code count, a third of all those in Boston were in Roxbury, Dorchester, and Mattapan - officials at firms such as H & R Block insist they're not targeting the poor. "A lot of the criticism is unfair. What we do is give our clients options," said Denise Sposato, a spokeswoman for H & R Block.First, she said, the firm's employees tell clients they can file their taxes electronically, and, if they have bank accounts, they can have their refunds automatically deposited within 14 days. If they don't have a bank account - and many don't - she said the tax preparers explain it may take as long as eight weeks to get a check in the mail.

Only after that, she said, do they raise the controversial option of a "refund anticipation loan." Depending on the size of their refund and their credit history, H & R Block will advance clients like Williams the money, subtracting a fee of about $100, or more in the case of larger refunds. That's on top of the usual tax preparation fee, which varies but often runs more than $100.

"For many of our clients, this is really just a convenience for them," Sposato said of the fee for the refund, comparing the trade off to someone who decides they would rather pay a high ATM fee than go without cash. "There are needs they have that may make the loan a smart choice for them."

But the loans have the effect of diverting billions of dollars from the poor to tax firms, said tax analyst Alan Berube of The Brookings Institution, a Washington think tank, who argues that the government bears some of the responsibility for the expenses because of the complexity of tax forms.

Last year, Berube published a study that found in 2001 H & R Block and other major tax firms earned $357 million alone by selling rapid refunds to earned-income tax recipients, more than double what they earned in 1998. In all, the study found, 7 cents of every dollar of such aid to the poor went to tax firms.

Part of the problem, he and others said, is the tax forms are so complicated many people would rather have a specialist do the work for them. Also, unless people file electronically, it can take a long time for refund checks to arrive from the government. One other problem: Nearly a quarter of those eligible for the tax credit - working families who earn $34,000 or less - either don't know about it or don't apply for it.

"So without a more effective system, tax firms can take advantage of a situation where people need cash and aren't aware of their options," said Berube, adding that in some parts of Dorchester and Roxbury a third of the working-poor residents seek rapid loans. "After a while, what happens is this becomes an annual cycle. At the beginning of the year, people look forward to getting a quick lump sum."

Though they know they would get back more money by filing electronically, Chuck and Trina White said they aren't eager to wait the eight weeks it might take by filing on their own. Like others, they prefer not to risk having their tax refund check stolen or lost in the mail.

Leaving the H & R Block on Uphams Corner after filing their taxes recently, the two said they're not happy to have forked over about $250 to the tax firm. But they insisted it was their best option.

"You get your check and it's in your hand," said Chuck White, 28, who described himself as a consultant. "That's peace of mind worth paying for."

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com.

Copyright, The Boston Globe